Marcus Liberty Adds Jersey Tetirement to Legacy of Impact

Posted Nov 13, 2025

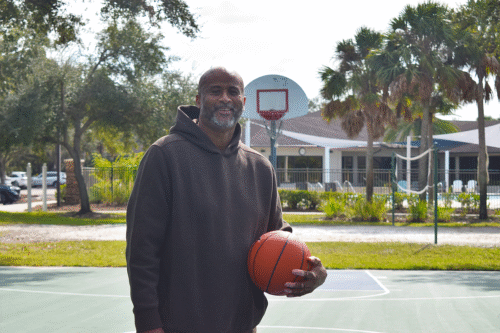

Marcus Liberty poses for a photo on Nov. 10 at Edgewater Park in Lakewood Ranch. He featured as a forward for the King College Prep boys’ basketball team which won the Illinois High School Association’s 1985-86 Class AA state championship.Recalling a moment or two from high school isn’t easy for Marcus Liberty. His archive of basketball memories is more expansive than most. That library spans not years, but decades.

Marcus Liberty poses for a photo on Nov. 10 at Edgewater Park in Lakewood Ranch. He featured as a forward for the King College Prep boys’ basketball team which won the Illinois High School Association’s 1985-86 Class AA state championship.Recalling a moment or two from high school isn’t easy for Marcus Liberty. His archive of basketball memories is more expansive than most. That library spans not years, but decades.

Buckets blurred together. Teams constituted an ever-rotating carousel. Most wins and losses are just numbers now.

It’s the people who have often been unforgettable. When he stepped onto the campus of his alma mater last weekend, he came face-to-face with many he hadn’t seen in quite some time.

Yet it was even more gratifying to meet those who he’s never hit the hardwood with.

“Just seeing that me playing basketball actually touched a lot of kids,” Liberty said. “I hear stories all the time, to this day, ‘Man, you’re the one who got me to bounce the basketball.’”

Liberty, now a 57-year-old Sarasota resident, had his No. 30 jersey retired Nov. 7 at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. College Preparatory High School in his hometown of Chicago. He helped their boys’ basketball team to the Illinois High School Association’s 1985-86 Class AA state championship, and as a senior, spearheaded an AA runner-up finish in 1986-87.

He made it all the way to the highest level of the sport, playing four seasons in the NBA with the Denver Nuggets and Detroit Pistons from 1990 through 1994. Liberty became a true journeyman during the eight years that followed, competing in Greece, Turkey, Puerto Rico, Sweden, Japan, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, France and Chile.

But the whirlwind came to a stop in 2002. These days, his on-court efforts concentrate on running Liberty Edge in Sarasota. He co-founded the youth basketball program alongside his wife, Christine Liberty, back in 2013.

“I get the most fulfillment out of seeing kids grow. That’s one thing I wanted to do, is be a mentor,” said Marcus Liberty. “Instead of being just a basketball coach, I wanted to be a mentor — someone who could share some of their ups and downs.”

“I get the most fulfillment out of seeing kids grow. That’s one thing I wanted to do, is be a mentor,” said Marcus Liberty. “Instead of being just a basketball coach, I wanted to be a mentor — someone who could share some of their ups and downs.”

There were no big-time ballers offering him guidance at a young age. He would’ve welcomed such a resource, but had none while growing up in the Chicago projects.

So Liberty grinded it out on his own. He put himself on the map at King College Prep, polishing off a stellar senior campaign in 1986-87 as the USA Today boys’ basketball player of the year and a McDonald’s All-American.

Boasting an elite skillset to match his 6-foot-8 stature, the small forward had the profile befitting of a Division I prospect. Illinois won the recruitment battle.

But Liberty had never planned on staying in state. His eyes were fixated on the East — the Big East, to be exact.

“It’s funny, I didn’t want to go to the University of Illinois,” Liberty said. “I wanted to go to Syracuse, and the reason why is because I wanted to be on television one way or another. They had a big broadcast school.”

He never played a minute in his first year with the Fighting Illini. In 1983, the NCAA adopted Proposition 48, setting minimum GPA and SAT/ACT score requirements which student-athletes had to meet in order to be eligible as freshmen.

It was first enforced in 1986 and kept Liberty off the court entirely. When he came back as a sophomore, he averaged 8.4 points, 3.9 rebounds and 1.2 assists per game in 1988-89.

That season, though, was about much more than himself — Illinois reached its first Final Four in 37 years. He played alongside fellow future pros in Nick Anderson, Kenny Battle, Kendall Gill and Steve Bardo. The team even defeated Syracuse in the Elite Eight to get there.

Liberty entered his name into the 1990 NBA Draft after a junior season in which he posted 17.8 points, 7.1 rebounds and 1.3 assists per game as a full-time starter. Denver snatched him up in the second round at pick No. 42 overall.

Reality about the league’s cutthroat nature hit him soon thereafter.

“The NBA is strictly a business. You have to know how to separate the two. You just can’t go in there and say, ‘You know what? I’m going to have fun,’” Liberty said. “They want you to be a professional. You’ve got to show up on time, you’ve got to stay late, you’ve got to put that extra work in. You’ve got to go outside in the community and build your own brand as well.”

He came off the bench in Year 1 with the Nuggets and averaged 6.7 points in 15.4 minutes per game, playing 76 contests in all. But he also felt an off-court calling many of his teammates did not.

Liberty served as community ambassador for the franchise. The forward had reached basketball’s most global league, and for the first time in his life, truly had a platform.

There was no hesitation to make the most of it.

“I remembered me as a kid,” Liberty said. “I would’ve loved to have an NBA guy be in my community, and be able to touch and talk to him and see what it was like to get to that high level.”

He maintains that mentality today, more than 20 years removed from his own playing days. It was precisely why both himself and his wife have sought to uplift and inspire athletes of the next generation through Liberty Edge.

There was a time when Liberty thought high school coaching was his avenue. From 2014-15 to 2017-18, he was the Out-of-Door Academy boys’ basketball coach, as well as the girls’ basketball coach in 2020-21.

Mentorship, though, is where his heart truly lies. He smiles extra wide when kids bring stories about how they aspire to dribble, shoot and jump like he once did.

To all those hopeful hoopers, he relays the same message.

“Don’t count on just basketball alone,” Liberty said. “Understand that ball will stop bouncing at some point in your life. You have to have a Plan B.”